Throughout history, the Maltese have often found themselves engulfed in the wars of foreign powers which over time have turned us into the warlike nation of hobbits we are today. In this more benign age, we are still constantly divided on matters of politics, sports and religion; and so, deep within the hoarding, bastion-clambering, church-going, saint-loving, football-obsessed, partisan-minded brain of the Maltese is a deep-rooted siege mentality which never really left our collective psyche.

We do love a good siege, especially the long, drawn-out, bloody variety. We love them because we’re good at them, and when we win a siege – which we invariably do – we don’t shut up about it, ever.

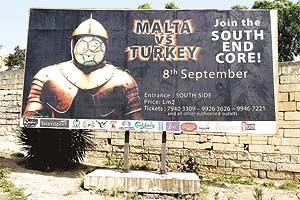

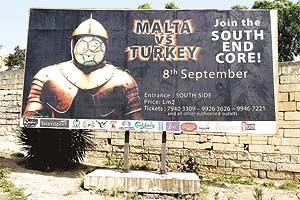

Promotional billboard leading up to Malta vs Turkey football match, 2007.

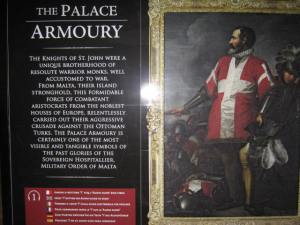

The suit of armour, such as the one in the billboard shown above, is a powerful expression of the quasi-mythical Knights of St John, often described as ‘warrior monks’, who were given lordship over Malta in 1530 by Charles I of Spain in exchange for a yearly tribute which included a Maltese Falcon. These Knights hailed from some of the noblest families in Europe, and therefore could well afford to be clad in the finest armour, some of which is today housed at the Palace Armoury in Valletta. The collection gives us a unique glimpse into certain aspects of 16th, 17th and 18th century warfare.

Snapshot of the Gardens of the Presidential Palace

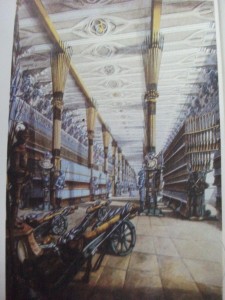

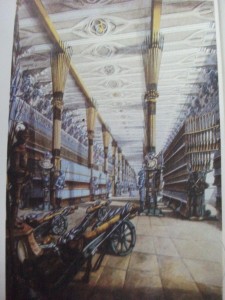

The previous location of the armoury up until recently dated from the 18th century and the rebuilding of the Palace under the rule of Grand Master Manuel Pinto da Fonsesca (1741-1773). This armoury was described in the 60s as “one of the biggest single halls for housing armoury in existence”. Few armouries around Europe can boast of being housed in their original setting. Unfortunately, the decision was made to move the items on display to their current location, a process which (I’ve been told by reliable sources) led to quite a few items being lost (stolen) <facepalm>. What was originally the Armoury is now the hall where the Maltese parliament convenes. When it comes to Malta’s heritage, one quickly acquires the skill of drawing a line at past sins, and concentrating on the present.

My visit to the armoury proved to be fascinating, and some of the objects on display were truly remarkable. The items were contained within two halls, with no thematic distinction between the two that I could pick up on. All the exhibits were professionally presented, with many displayed in protective glass showcases. The audio guide that was included in the price functioned perfectly, and provided a commentary for the more significant objects on display. Some of the cannons had intricate designs on them, such as the one shown below which seems to bear some sort of coat of arms. I’m sure that each individual cannon had a story to tell, which wasn’t explained, but the richness of the cannon in the photograph below does indeed speak for itself. It speaks to us of glory, god and power – and a world where a hail of cannon fire was considered to be a more effective solution to a dispute than diplomacy.

‘Beautiful Cannon’, said no invader of Malta, ever.

One of the most interesting exhibits at the museum was the collection of Ottoman swords, armour and apparel, given pride of place in a very prominent and imposing showcase. The 16th century ottomans (generally referred to by the Maltese as it-Torok) are deeply embedded in our collective consciousness, though they are often caricaturised as in the carnival parata,which reduces the glorious and bloody violence of the great siege to a rather camp display of kids hopping about in circles, brandishing foil-covered cardboard swords.

Maltese parata.

The colourful silk fabric, wicked-looking curved swords and circular shields are apparently not far off the mark, though the reality was far more badass:

Ottoman armour and weapons.

Much of the average Maltese person’s body of knowledge from this period is focussed on the knights. To see this ottoman armour and weaponry up close gives one a glimpse of a past culture whose destiny was interwoven with that of our land and ancestors. In all probability, whoever used these weapons and armour died a long way from home, on our shores fighting in the great siege. Their bodies have become a part of the fabric of our soil, and their stories a part of the fabric of our mythology. Maybe I’m over-thinking things but these are the sort of thoughts that resonate so deeply with me, and make museums (to my mind) such important places for our culture and society.

Beyond the impressive ottoman armour display and elaborate cannons were numerous showcases displaying equally fascinating objects. I was very disappointed to have missed out on the opportunity of seeing a breast plate that was worn by none other than La Vallette – (or de Vallette, or de la Vallette – no one seems to be sure) – as this was temporarily being displayed at the Museum of Archaeology, but there were plenty of other objects which made up for this:

Sticks and stones may break my bones, but a long sword in the hands of a trained swordsman will decapitate me with a single swipe.

‘The best a man can get.’

According to the descriptions, these swords were used in the great siege, and are to my mind among the most enduring symbols of Medieval Christian warrior knights. I’ve always found it strange how ottoman swords differ so greatly from their Christian counterparts. I recall reading an apocryphal tale about a meeting in the desert between King Richard the Lionheart and Saladin. The two monarchs were comparing their swords (as men do), whereupon to show off his blade’s superiority, Richard called for a mace to be placed before him. He drew his sword and with a mighty swing split the iron handle of the mace in two. Saladin, seemingly unimpressed, drew from his pocket a silk handkerchief, which he nonchalantly tossed up into the hot desert breeze. Before the fluttering handkerchief had time to settle onto the sand, Saladin’s sword was drawn and with a quick flourish had sliced through the silken cloth. Thus, the characters of the two blades were aptly illustrated, and it was agreed that the size of a sword isn’t as important as how you use it.

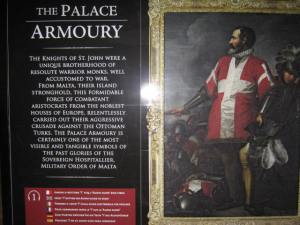

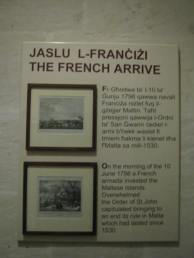

Beyond the undoubted richness of the exhibited items themselves and the professional way in which they were presented, I feel that more effort could be put towards establishing the objects within a narrative, with key moments such as the Knights’ expulsion from Rhodes, the Great Siege and the arrival of the French clearly explained (preferably through audio-visual means), but if that’s not possible, then placards similar to the one shown below would suffice.

Placard which greets visitor on entering Armoury.

Creativity is not necessarily a quality most people would associate with museum curation, but in fact, modern museums are constantly on the lookout for ways and means of giving their visitors exciting and interactive experiences. In light of the notoriously poor budgets afforded to Maltese museums, a little must be made to go a long way, and the exhibit shown in the photograph below is a wonderful example. Two stone weights placed in front of the exhibit allow the visitor to feel the difference in weight between the two cannon balls. It’s simple but effective. I doubt whether a single person walked past this exhibit without curiously comparing the different weights. Humans love touching things, picking them up, examining them, poking them, and constantly staring at objects through glass can be frustrating.

Difference in weight between lead and stone.

In my opinion, the more bells and whistles a museum has, the better – for instance, another addition which could be added to the Armoury might be a small screen with a basic animation or slideshow showing how cannon is loaded and fired. I’m full of great ideas like that. All in all, however, I was pleased with the Malta Palace Armoury and thought that it did justice to the warrior legacy of the order. The fanatical patriot in me would like to see more than just two rooms devoted to weaponry. If one considers this rendering of the original armoury by Brockdorf in the 19th century, one can safely assume that the armoury has been slightly whittled down over the years.

F. Brockdorff: A general view of the Armoury (19th century watercolour).

Sir Guy Francis Laking wrote up the first inventory of the armoury in 1927 – and even then, a lack of detail in the object descriptions means we are not totally sure of whether objects were lost since 1927, particularly during the 1974 transfer. Most looting was done by Napoleon’s troops during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, there’s no real need for such bleak ponderings as the Armoury is today still a jewel of Maltese heritage that I would recommend to anyone. If medieval battlefield paraphernalia is what gets you off, then you’ll love this museum. If you’re an Iron Man fan, you might also be interested, but mostly, if you’re fascinated by the military might of the Order of the Knights of St John, then plan a visit to the Palace Armoury as soon as you possibly can.